Hammersmith & Fulham is one of the most proudly diverse boroughs in the country. But what was life like for Black residents during the Second World War?

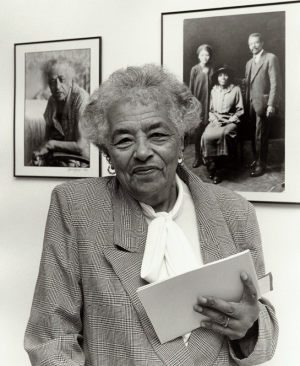

Author Stephen Bourne, a founder member of the Black and Asian Studies Association, shone a light on the subject when he interviewed his aunt, Esther Bruce, a Black working-class Londoner who lived in Fulham. She was honoured with a blue plaque near Charing Cross Hospital in early 2022.

In 1991 they co-wrote a book about her experiences, The Sun Shone on Our Side of the Street, as part of the Hammersmith & Fulham Community History series.

The book won the Raymond Williams Prize for community publishing, and was described by the Caribbean Times as inspirational and enlightening.

Strong and resourceful

Esther's father Joseph Bruce had settled in Fulham in the Edwardian era, and Esther was born here in 1912. He had come to Britain from the colony of British Guiana (now Guyana) in South America.

Esther left school at 14 to work as a seamstress, making dresses in the 1930s for the likes of popular black American singer Elisabeth Welch, perhaps best known for songs such as Stormy Weather and Love for Sale.

In 1941, tragedy struck. Esther's father, Joseph, was killed during an air raid, so Esther was 'adopted' by her (white) grandmother, Granny Johnson.

"She was like a mother to me; she was an angel," Esther recalled. Added Stephen: "For the next 11 years Aunt Esther shared her life with granny (who died in 1952), and became part of our family.

"During the Second World War, Aunt Esther worked as a cleaner and fire watcher in Brompton Hospital. She helped unite her community during the Blitz… and having relatives in Guyana proved useful when food was rationed!"

Esther recalled the hard times keeping the family fed during the war. "Food was rationed. Things were so bad they started selling whale meat, but I wouldn't eat it. I didn't like the look of it. We made a joke about it, singing Vera Lynn's song We'll Meet Again with new words: 'Whale meat again!'

"Often Granny said: 'We could do with this. We could do with that.' So I wrote to my dad's brother in Guyana. I asked him to send us some food. Two weeks later a great big box arrived, full of food! So I wrote more lists and sent them to my uncle. We welcomed those food parcels."

In 1944 Adolf Hitler sent doodlebugs over. Said Aunt Esther: "When the engine stopped I wondered where it was going to drop. It was really frightening because they killed thousands of people. A doodlebug flattened some of the houses in our street. Luckily our house was alright, even though we lived at number 13!"

Always remembered

Stephen said: "In the late 1980s I began interviewing Aunt Esther, and in the course of many interviews I uncovered a fascinating life history spanning eight decades.

"Aunt Esther gave me first-hand accounts of what life was like for a Black Londoner throughout the 20th century. A friendly, outgoing woman, my aunt integrated easily into the multicultural society of post-war Britain.

"In 1991 we published her autobiography, Aunt Esther's Story, and this gave her a sense of achievement and pride towards the end of her life.

She died in 1994 and, following her cremation, my mother and I scattered her ashes on her parents' unmarked grave in Fulham Palace Road cemetery. Granny Johnson rests nearby."