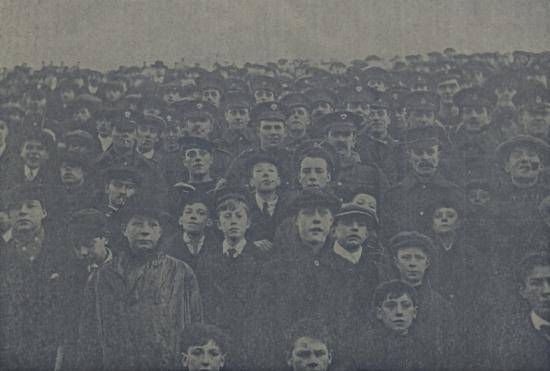

The first post-war Chelsea side in 1919

On the Centenary of Armistice, guest blogger and historian Alexandra Churchill looks at the sacrifices made by those connected with Chelsea Football Club in the First World War.

Chelsea Football Club, formed in 1905, was still in its infancy at the outbreak of the Great War.

There had been preliminary suggestions that it was improper for the Football League to continue, and an impassioned campaign began to suppress the playing of professional matches in particular.

In 1914, though, Britain had not yet reached the point at which the she needed to conscript all of her men into uniform – and the 1914-15 season began.

Chelsea, like all clubs, felt the strain of wartime operation. The club had calculated that a minimum turnover of £700 per game was required to keep it afloat, but crowds were thin.

For those that did attend, there was a heavy emphasis on fundraising. A small legion of local young ladies wearing bright sashes volunteered to help convince supporters to empty their pockets.

They floated through the crowd at matches, shouting ‘pay up and look pleasant!’ and ‘do your bit for the boys who are doing their bit for you!’

Wounded soldiers were entertained at Stamford Bridge, as were numbers of Belgian refugees who were most enthusiastic about the team’s fortunes. Thousands of soldiers were encamped about London and a trip into town for the football was a welcome weekend outing.

While the press continued its endeavours to demonise football, the players at Chelsea had joined those of clubs up and down the country in preparing for the eventuality that they may have to go to war.

After comedic beginnings, rifle drill at Chelsea was beginning to yield results.

Presided over by the apparently terrifying figure of Colour Sergeant Meacher, a ‘very candid critic’, the awkward ‘regiment’ of players, club officials and friends who were too old to enlist lined up in front of him. Bravely they weathered his booming voice under the floodlights in front of the club’s offices.

A group of Chelsea fans made an effort to enlist together in the Royal Sussex Regiment, led by a clerk named Clifford Whitley, who was employed in the offices of the Daily Mail.

But the major contribution made by Chelsea in recruitment was to help found the 17th Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment.

On 15 December 1914, 500-odd men congregated at Fulham Town Hall to discuss the formation of the 17th Middlesex Regiment.

There were players present from a host of clubs, including Chelsea, Fulham, Clapton Orient, Bradford City, Brighton.

As the meeting concluded thirty-five players, three of them on Chelsea’s books, had signed up for this ‘Footballers Battalion.’

At Christmas the local Chronicle was touting for fans to join it under the heading ‘Any more Chelseaites for Berlin in the spring?’ Men were encouraged to go to the club office to ‘sign on, like an international footballer.’

As 1915 dawned Chelsea were fourth from bottom of the league, but the 1914/15 season would host the only FA Cup run in the competition’s history played out while the country was embroiled in a World War. And the Pensioners reached their first final.

The amount of uniformed spectators in the crowd at Old Trafford lent it the nickname of the ‘Khaki Cup Final.’ At half-time, the band played ‘Tipperary’; and a collection was made for the Red Cross - sheets held out for fans to toss pennies onto.

The light was fading fast when Sheffield United ran out 3-0 winners.

Amateur football was largely petering out of its own accord. By late April still no decision had been taken and in fact it would not be until July that it was ordained that there would be no more competitive matches.

No more contracts employing men to play for a living were to be drawn up. Professional football was now on indefinite hiatus.

At Stamford Bridge the makeshift, amateur London Combination league was a profitable venture in entertaining a crowd for the rest of the war. The Blues won it comfortably in 1915/16, and again by a single point in 1917/18 at the expense of West Ham.

The club searched for other ways to fill Stamford Bridge while the war raged on, including hosting a raucous baseball match between the US Navy and US Army: attended by the King on 4 July 1918.

Familiar faces at Stamford Bridge: of fans, players and staff associated with the club, would not return after the armistice. But the Blues survived being shaken to the core by events on a worldwide scale.

One hundred years later Chelsea Football Club lives on.

And sharing the same traditions as long ago, in the remembrance of all of those associated with the club at the centenary of the Great War, so too does a sense of gratitude for those who left the pitch and terraces: to fight, and never return.

Buy Alexandra Churchill’s book – Over Land and Sea: Chelsea FC and the Great War.

Read more on the First World War

- ‘Tommies’ stand guard at town hall ahead of Remembrance Sunday

- Remembering H&F’s women workers of the ‘home front’

- Fulham Camerata concert marks end of First World War

- Blog: First World War left its mark on Fulham

Want to read more news stories like this? Subscribe to our weekly e-news bulletin.